As suggested in this February 25th Wall Street Journal article ("China Feels the Pinch From Tighter Credit"), Chinese central bank regulators are curbing lending to the country's regional governments. These actions, along with a myriad of other policy iniatives including raising the reserve requirement twice this year, prohibiting lending by state banks for the last week in January (after 1.4 trillion yuan of new loans were extended - 20% of the 7.5 trillion yuan target for the entire year), and eliminating the practice of banks selling loans to off-balance trust companies, all reflect increasing concern by government officials that China's overheated economy needs to be restrained.

While local governments are generally prohibited from incurring debt, most set up local companies to take on outside financing. Comforted by their land holdings and an implicit guarantee from the central government (sounds similar to how Fannie/Freddie were able to access cheap capital!), many of China's largest banks lent freely to these investment companies to finance significant infrastructure development.

As noted in the article:

Estimates of the total debt accumulated by investment vehicles set up by local governments range from six trillion yuan (around $878 billion) widely cited in the Chinese media, to the 11 trillion yuan calculated by Northwestern University professor Victor Shih. Those sums—on the same order of magnitude as all the official debt of China's central government—have drawn high-level concern.

Liu Mingkang, China's chief bank regulator, followed up in a nationwide conference call with bank executives on Jan. 26, telling them to "fully assess and effectively guard against risks from local government financing platforms."

The Shanghai Securities News reported Wednesday, citing unnamed sources, that banks had been ordered to stop issuing new loans to investment vehicles that are backed only by local governments' future revenue and have no registered capital.

While most skeptics of a potential Chinese credit bubble point to the country's ample foreign currency reserves and relatively low level of government debt to GDP, it is important to realize how much debt resides "off-balance" in the form of loans to these local investment companies (which as noted before have the implicit guarantee of the federal government). The first evidence of a deflating credit bubble will be when one of these regional governments can't roll over their debt. Many will point to the "excesses of this one local investment company" and give the standard refrain uttered at the beginning of the suprime meltdown that "the blowup is isolated and will not spread to the rest of the economy." However, as the events of 2007-2009 taught us, bad loans from one sector of the economy inevitably restrict lending to other seemingly healthy parts of the economy as banks work to restore their capital reserves. The systemic problems caused by China's highly concentrated quasi-government banking system will only heighten the spread of this contagion.

A February 9th op-ed piece in the Wall Street Journal Asia edition ("China's 8,000 Credit Risks") by Professor Victor Shih does an excellent job explaining the mounting problems of China's regional investment companies.

Friday, February 26, 2010

Monday, February 22, 2010

Historically Low Mortgage Spreads

Below is a great chart courtesy of David Rosenberg of Gluskin Sheff showing the historical spread of 30 mortgages to treasuries. Historically, this spread is 150bps, but now stands at a measly 20bps. As discussed several times on this blog, the huge compression in mortgage spreads to treasuries reflects the Federal Reserve’s $1.25 trillion MBS buying program, which is slated to end by the end of March. While the Fed could decide to extend the program or use Fannie & Freddie as a backdoor conduit to support the mortgage market (since both organizations now have more flexibility on when they have to shrink their balance sheets), the prospect of higher mortgage rates seems very likely as we progress through 2010.

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

Japan Displaces China as Largest Holder of Treasuries

Japan overtook China as the largest foreign holder of US Treasury debt last month. China reduced its holdings of treasuries by $34 billion in December and now holds $755.4 billion of US government debt. Conversely, Japan added to its holdings by $11.5 billion during the month, ending the year with $768.8 billion of treasuries in its portfolio.

In the article, “Japan Reclaims Title of Top Treasury Holder”, The WSJ highlights the mounting concerns that China’s waning interest in US treasury debt could have for our ability to finance our growing deficits.

The purchasing behavior of China has been troubling to some analysts and potentially to a U.S. government that is seeking to borrow a record amount this fiscal year. The latest shift would seem to reinforce market worries that China is tiring of its role as a key creditor to the U.S. amid rising budget deficits and tensions between Beijing and Washington.

While fiscal problems in Europe could provide a short-term boost to the United States, particularly from “safe haven” buyers, the long-term threat from declining support from China (seeking diversification) and Japan (as the country inevitably shifts from a creditor to a debtor nation) should be the cause of great concern for investors.

In the article, “Japan Reclaims Title of Top Treasury Holder”, The WSJ highlights the mounting concerns that China’s waning interest in US treasury debt could have for our ability to finance our growing deficits.

The purchasing behavior of China has been troubling to some analysts and potentially to a U.S. government that is seeking to borrow a record amount this fiscal year. The latest shift would seem to reinforce market worries that China is tiring of its role as a key creditor to the U.S. amid rising budget deficits and tensions between Beijing and Washington.

While fiscal problems in Europe could provide a short-term boost to the United States, particularly from “safe haven” buyers, the long-term threat from declining support from China (seeking diversification) and Japan (as the country inevitably shifts from a creditor to a debtor nation) should be the cause of great concern for investors.

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

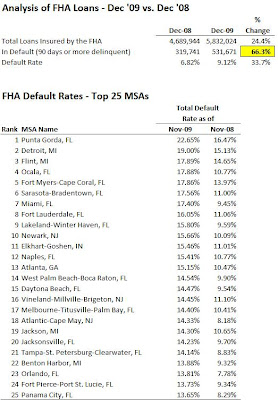

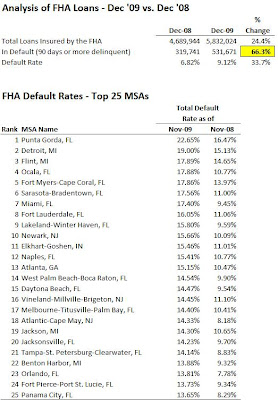

Another Rise in FHA Default Rates

In its latest report to HUD, the Federal Housing Administration disclosed that its default rate (loans more than 90 days delinquent) increased to 9.12% as of December 2009 vs. 6.82% in the prior year. More specifically, 531,671 of the 5.8 million loans insured by the FHA were in default, a staggering 66% year-over-year increase. As expected, Florida led the pack, with the state comprising 16 of top 25 most delinquent MSAs. Michigan had 4 cities in the top 25 and New Jersey had 3. The MSA with the highest default rate was Punta Gorda FL, with nearly 23% of its FHA-insured mortages at least 90 days or more in arrears.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)